By John Blyler, Contributing Editor

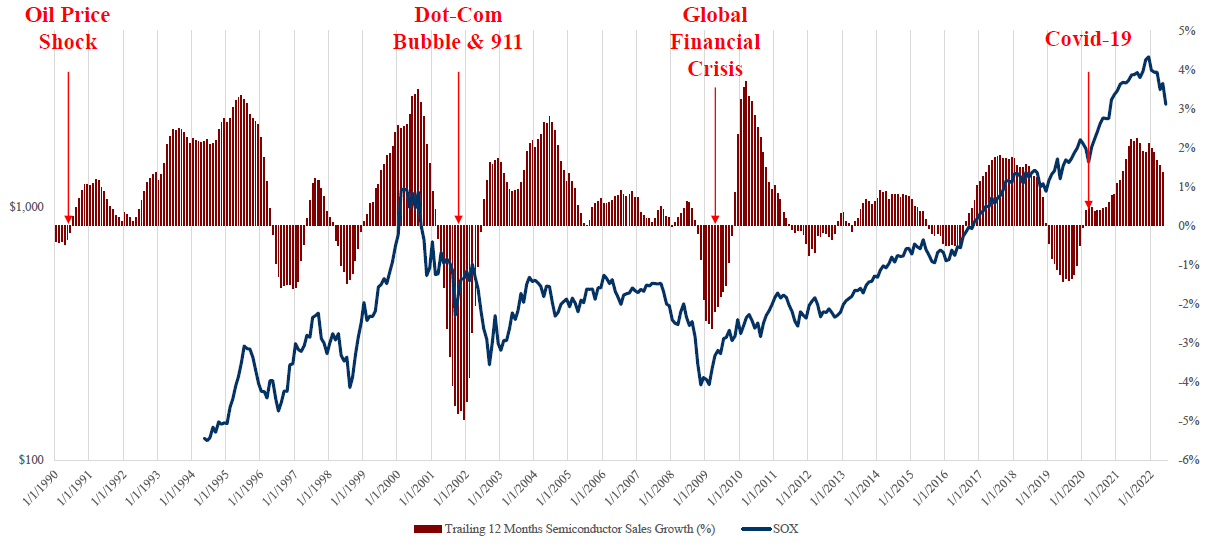

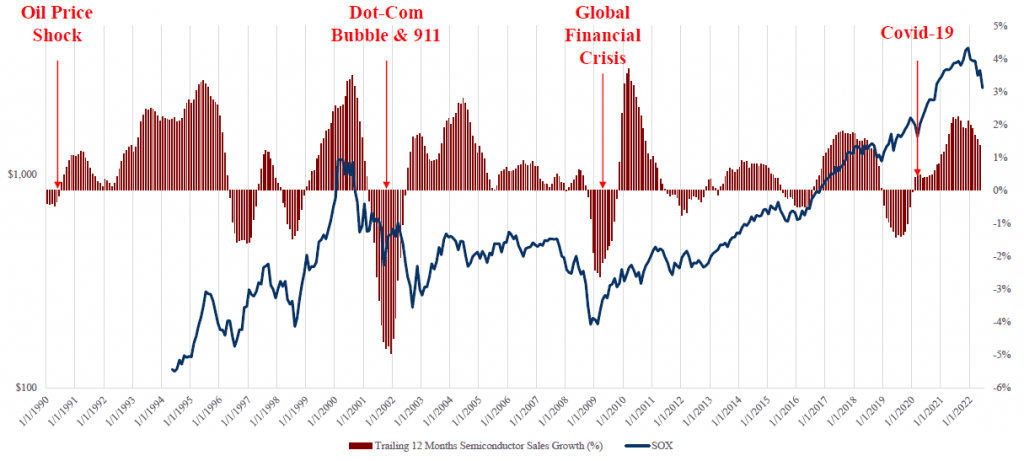

The semiconductor bulls are getting nervous. Six months ago, they ruled the market, and now, that’s changed thanks to ongoing supply chain issues, dwindling demand, and geopolitical clashes. Recently, there have been indications that the semiconductor space is shifting downward due to growing inventory stockpiles and canceled orders at the major fabs. Veterans in this market stifle a yawn at such revelations, chalking it up to the cyclical nature of the business. Shortages are real and painful until they become surpluses – which has been the pattern for the last 50 years.

But not all segments of the semiconductor market are poised for a surplus downturn. Two seem immune to the larger cyclical pattern of bust-to-bust. Which segments are these? To answer that question, Semiconductor Digest turned to Charles Shi, Principal Research Analyst at Needham & Company. What follows is a portion of that interview prior to his presentation at DAC 2022. – John

John Blyler: The semiconductor general shortage-to-surplus cycle is well understood. Is there something happening this time that makes this occurrence different?

Charles Shi: One thing that has affected the cycle over the last 2 to 3 years was the appearance of a global pandemic. As COVID began to strike the world’s populations and wreak havoc on the industrial markets, the semiconductor world was recovering from its last downturn. COVID helped the semi market grow by causing enormous demand destruction in the service sectors of the world’s economies. Instead of traveling, staying in hotels, and gathering at restaurants, people stayed at home and spent more time and money on physical things, most of which contained semiconductor content. And the US government stimulus checks probably helped the demand for electronic-based devices even more.

Now we have entered a different stage as economies are opening up, and people are more comfortable traveling and dining out. We have moved back to a services economy instead of one based more on physical goods. And the Feds have removed the stimulus checks and are tightening the cost of money to bring down rising inflation.

All of these are causing an abrupt change in the macro-environment. But the semiconductor industry cannot change that fast. It has too much inertia. Building new fabs to increase capacity when demand is rising takes two years to achieve. Also, new fabs require complex and expensive chip-making equipment, and since many countries are adding new fabs, the lead time for the necessary equipment has also increased.

John Blyler: But that’s not the whole story for semis, as you mentioned last year. Isn’t one part of the market holding strong and even growing?

Charles Shi: It’s a different tale in the world of EDA chip development tools and intellectual property (IP). These subsegments – comprised of companies like Synopsys, Cadence, Siemens EDA, and Ansys – initially fell with the rest of the semiconductor market in early 2022 but quickly stopped falling after a few months. The key reason for this shift is that EDA and IP companies don’t sell to consumers but chip companies.

It works like this: When companies see demand drop, they will ask their suppliers to make fewer chips. This scenario happened when the automotive manufacturers cut chip orders at the pandemic’s start. But drastically cutting unneeded semiconductor supplies comes at a price, as the car companies later realized when their markets returned. It took time to restart the chip-making process, and hence a shortage occurred.

This is generally not the case for EDA tools and IP. One of the last things chip companies cut during a downturn is research and development (R&D) for new products. In fact, it may be the one expenditure that is increased during a technology downturn. And that is the sweet spot for EDA and IP.

Companies will continue to spend – or increase spending – on-chip development tools and IP to prepare for the eventual demand upturn that will come, as demonstrated time and time again by the historical cycle. This is why Wall Street is not seeing much of an impact on the stocks of Synopsys and Cadence.

John Blyler: Aside from the cyclical economics of chip development, what complexity issues are different now?

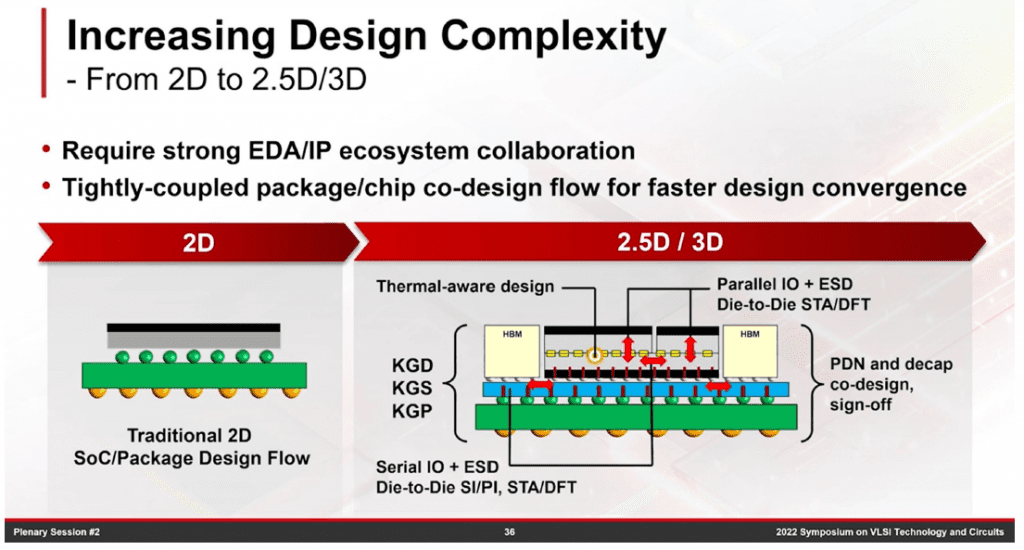

Charles Shi: The increasing complexity of designs continues to drive the need for more powerful tools and related IP libraries as well as new implementation strategies such as stacked die technologies, special packaging, and other assembly types. These evolving system-level approaches have changed the traditional meaning of SoC from “system-on-chip” to “system-of-chips.” Conveniently, the acronym is still the same.

As further recognition of this change, the chairman and co-CEO of Synopsys, Aart de Geus, presented a keynote address at the 2021 Synopsys Users Group (SNUG), which observed that Moore’s law scaling is now blending with innovations that leverage systemic complexity. He coined the term SysMoore as a shorthand way to describe this new design paradigm of heterogeneous integration.

The increasing design complexity can be seen in the shift from 2D to 2.5D/3D integrated systems, which require strong EDA and IP ecosystem collaboration to be successful (see Figure 2).

John Blyler: In addition to these economics and complexities, the global move toward digitization must also play a part.

Charles Shi: Certainly –consider this interview with Dr. Walden Rhines that I conducted as part of our Jun 1, 2022 “Semiconductor and Semiconductor Equipment report:

“One overwhelming driver that exceeds all others (for the growth of EDA) is the entry of systems companies into the world of integrated circuit design,” explained Dr. Rhines. He points to systems companies entering chip design as the #1 driver for EDA’s recent growth accelerations. Dr. Rhines says before systems companies came in, people could reliably predict EDA market size being constantly at 2% of the semiconductor revenue. But now, with a new set of customers outside the traditional semiconductor industry, EDA growth, in some sense, has decoupled from semiconductor growth. Dr. Rhines sees that 20-25% of the total foundry wafers in the world today are already bought by systems companies and the number may continue to grow.

The long-term growth story for EDA and IP is not changing in the near term. Indeed, EDA and IP look to outperform the rest of the industry because companies will not slow down R&D, especially in a semiconductor down cycle.

John Blyler: How will geopolitical challenges like those between the US and China affect the global EDA tool and IP markets?

Charles Shi: Whatever their motivation, the Chinese continue to spend on semiconductor self-sufficiency. Indeed, neither the US nor China can completely cut off ties. The industry supply chain is too closely interwoven – at least for now.

The main reason is that you don’t have a viable, indigenous EDA accompany that can cover all aspects of the chip development in China. You always need to go Synopsis, Cadence, or Ansys for tools and IP.

The importance of IP can not be underestimated. IP allows designers to kick-start their designs immediately. Plus, much of the IP is already silicon verified, i.e., fab ready. And there’s no point in reinventing the wheel. Incorporating IP lets designers focus on the features and functionality that differentiate them from their competitors.

For these reasons, I don’t think there will be significant negative EDA and IP growth in China.

John Blyler: Thank you.