Researchers have advanced a decades-old challenge in the field of organic semiconductors, opening new possibilities for the future of electronics.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge and the Eindhoven University of Technology, have created an organic semiconductor that forces electrons to move in a spiral pattern, which could improve the efficiency of OLED displays in television and smartphone screens, or power next-generation computing technologies such as spintronics and quantum computing.

The semiconductor they developed emits circularly polarised light—meaning the light carries information about the ‘handedness’ of electrons. The internal structure of most inorganic semiconductors, like silicon, is symmetrical, meaning electrons move through them without any preferred direction.

However, in nature, molecules often have a chiral (left- or right-handed) structure: like human hands, chiral molecules are mirror images of one another. Chirality plays an important role in biological processes like DNA formation, but it is a difficult phenomenon to harness and control in electronics.

But by using molecular design tricks inspired by nature, the researchers were able to create a chiral semiconductor by nudging stacks of semiconducting molecules to form ordered right-handed or left-handed spiral columns. Their results are reported in the journal Science.

One promising application for chiral semiconductors is in display technology. Current displays often waste a significant amount of energy due to the way screens filter light. The chiral semiconductor developed by the researchers naturally emits light in a way that could reduce these losses, making screens brighter and more energy-efficient.

“When I started working with organic semiconductors, many people doubted their potential, but now they dominate display technology,” said Professor Sir Richard Friend from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, who co-led the research. “Unlike rigid inorganic semiconductors, molecular materials offer incredible flexibility—allowing us to design entirely new structures, like chiral LEDs. It’s like working with a Lego set with every kind of shape you can imagine, rather than just rectangular bricks.”

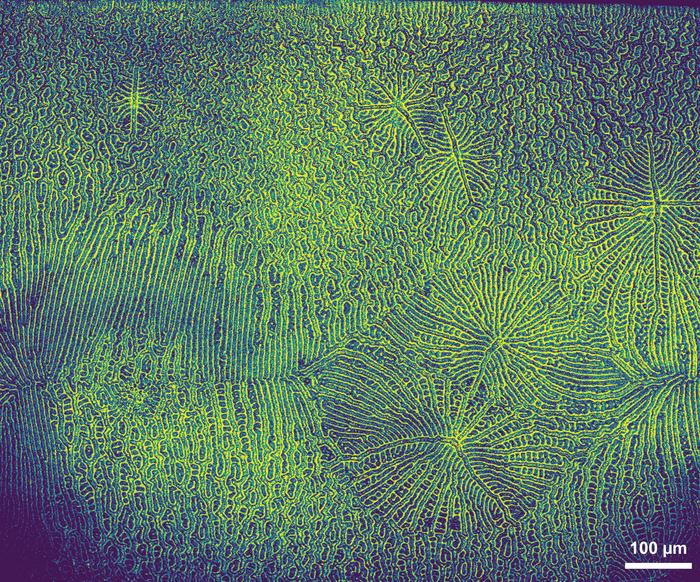

The semiconductor is based on a material called triazatruxene (TAT) that self-assembles into a helical stack, allowing electrons to spiral along its structure, like the thread of a screw.

“When excited by blue or ultraviolet light, self-assembled TAT emits bright green light with strong circular polarisation—an effect that has been difficult to achieve in semiconductors until now,” said co-first author Marco Preuss, from the Eindhoven University of Technology. “The structure of TAT allows electrons to move efficiently while affecting how light is emitted.”

By modifying OLED fabrication techniques, the researchers successfully incorporated TAT into working circularly polarised OLEDs (CP-OLEDs). These devices showed record-breaking efficiency, brightness, and polarisation levels, making them the best of their kind.

“We’ve essentially reworked the standard recipe for making OLEDs like we have in our smartphones, allowing us to trap a chiral structure within a stable, non-crystallising matrix,” said co-first author Rituparno Chowdhury, from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory. “This provides a practical way to create circularly polarised LEDs, something that has long eluded the field.”

The work is part of a decades-long collaboration between Friend’s research group and the group of Professor Bert Meijer from the Eindhoven University of Technology. “This is a real breakthrough in making a chiral semiconductor,” said Meijer. “By carefully designing the molecular structure, we’ve coupled the chirality of the structure to the motion of the electrons and that’s never been done at this level before.”

The chiral semiconductors represent a step forward in the world of organic semiconductors, which now support an industry worth over $60 billion. Beyond displays, this development also has implications for quantum computing and spintronics—a field of research that uses the spin, or inherent angular momentum, of electrons to store and process information, potentially leading to faster and more secure computing systems.

The research was supported in part by the European Union’s Marie Curie Training Network and the European Research Council. Richard Friend is a Fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge. Rituparno Chowdhury is a member of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge.