John Blyler, Senior Contributing Editor

The continuing economic death of Moore’s Law is resulting in a simpler semiconductor value chain. Large system companies will take advantage of this change by cutting the middleman. What will this mean for the EDA-IP providers? How will they survive? Semiconductor Digest’s John Blyler talked with Charles Shi, Principal Research Analyst at Needham & Company, to answer that question. What follows is a portion of that interview before his keynote presentation at DAC 2023.

John Blyler: Your past projections have been accurate. What does your crystal ball see for EDA-IP in the near and long term?

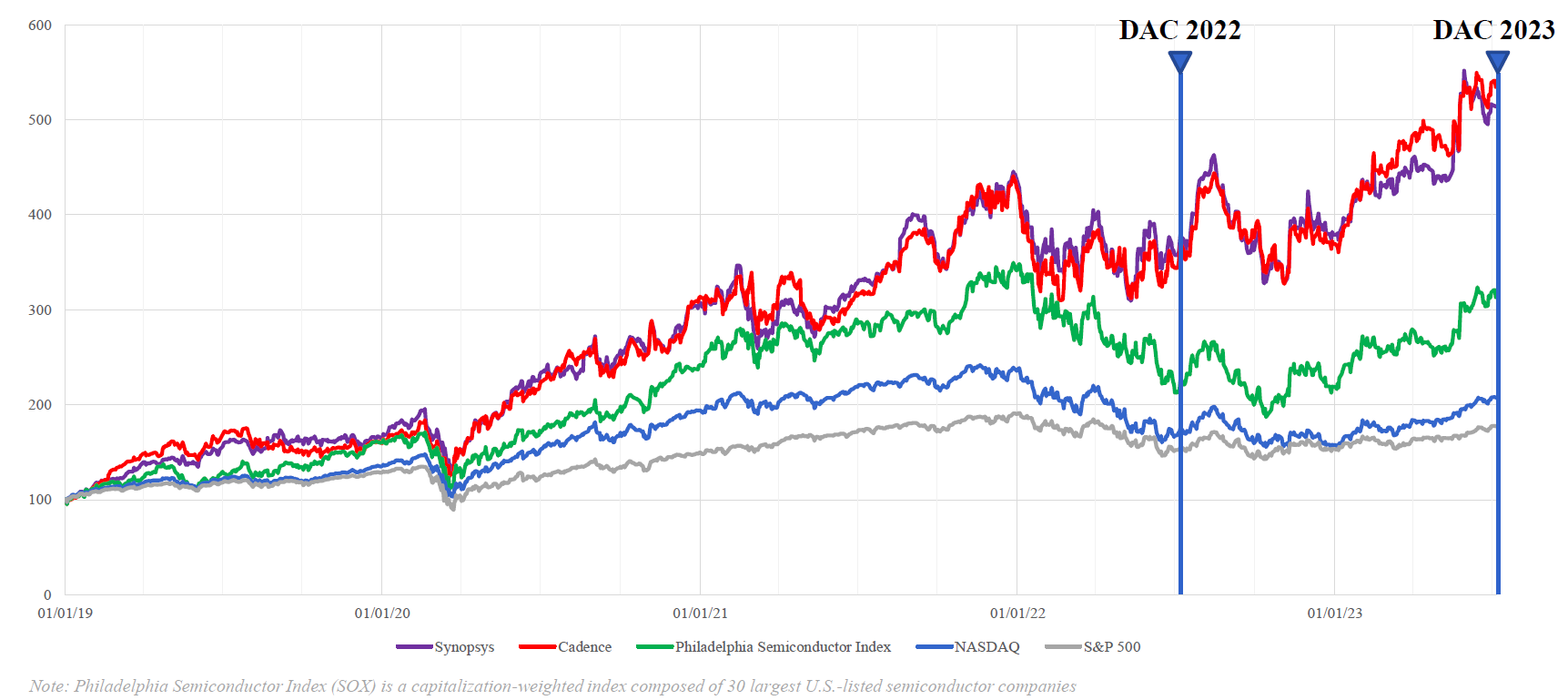

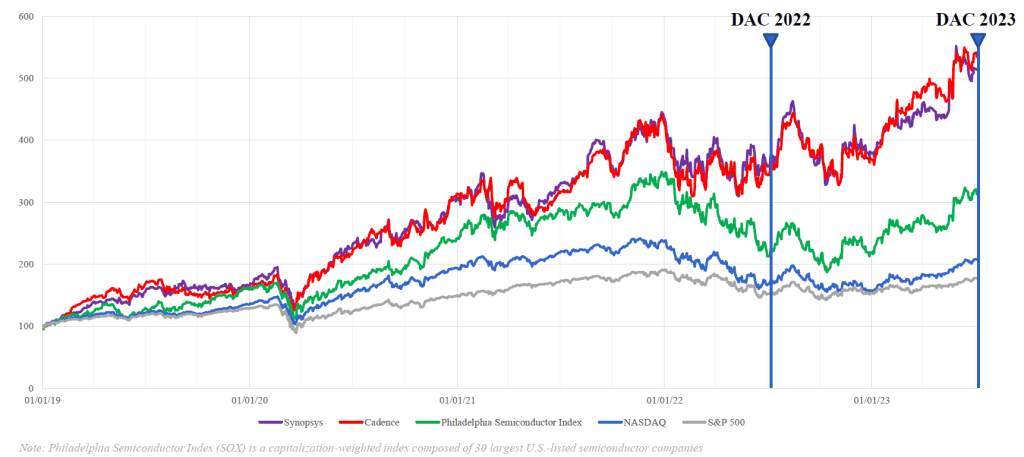

Charles Shi: I’m maintaining most of my predictions from last year, but I will add an important update for this year. Let’s start with the near-term forecast. The previous DAC in July 2022 began a cyclical semiconductor downturn. History tells us that these downturns last roughly one year, so we should start to see numbers improve, and good news arrives in the second half of this year.

John Blyler: Was there no bright spot during the downturn of the last year?

Charles Shi: Although most of the numbers were down – including volume and (mostly) price – the one bright spot was that capital and R&D spending stayed up. I’m not including memory companies in this summary as the memory industry is hyper-cyclical. Also, I’ve removed Intel as it has its unique, idiosyncratic problems. Even with these caveats, R&D spending was up 6% this year. It has been very resilient to this downturn, almost bulletproof.

John Blyler: And in the long term?

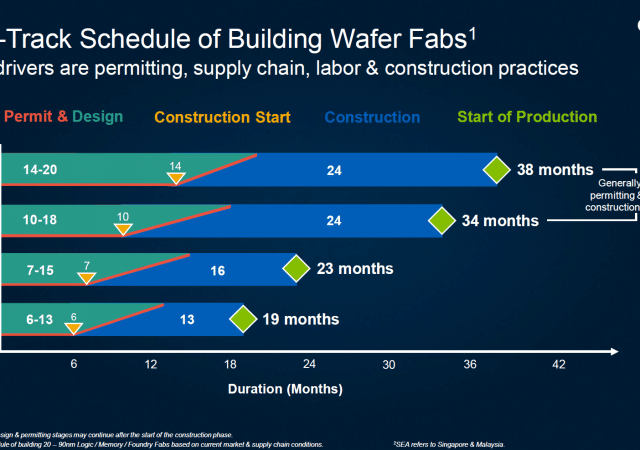

Charles Shi: As you may remember from my previous forecasts, my take has been that the industry is slowing down. Manufacturing will consolidate into one or two foundries – of course, how Intel will fare in this space remains to be seen. Other noteworthy trends are that transistor scaling is slowing down, and thus, 3D-IC designs and chiplet technologies are becoming more important.

What’s relatively new this time is the move to more domain-specific computing, which means that customers will either buy semi-custom chips from chip companies or design (and even manufacture them) in-house, like Apple, Google, and the rest of the system companies.

John Blyler: The cost of designing chips is high. In what scenarios does it make sense for a company to take on that cost?

Charles Shi: I’m doubling down on this trend, namely, that systems companies will see “design in-sourcing” as a better choice, especially for artificial intelligence (AI) chips. It’s a way to deal with the rising cost of chips at the lower process nodes. The challenge is that if these companies do nothing, the cost of silicon will eat into every project. One way to save costs will be to cut out the middleman, which, unfortunately, means traditional semiconductor companies.

But this approach is not as easy as it might seem. The hurdle is the upfront design cost. A popular chart shows a chip design for 5 nanometers (nm) will cost $500 million. So, chip design will not be for everyone except for a few companies in specific high-volume end markets, such as Apple in the smartphone industry.

Aside from very high-volume markets, the other situation where designing application-specific chips makes sense is where the value of the chip is very high. For example, the Nvidia A100 chip costs between $10k to $20k per chip. But if you can design the whole thing, the price will start to go down. In this case, the cost for TSMC to manufacture will be around $600 to $700 per ship for middle-volume quantities. Yes, the initial hurdle of a $500 million design cost is high, but making your own chip may be cheaper for certain high-value chips, e.g., AI chips for data centers.

John Blyler: Is cost the only factor in designing a chip in-house?

Charles Shi: Cost is a big factor but not the only one. The other involves the strategic value of having a chip designed for your software. The issue here is who owns the software? It’s not the chip companies but rather the system companies. But this is part of a larger trend over the last five years, where big system companies (e.g., Apple, Google, Microsoft, Meta, Tesla, Huawei, Baidu, etc.) have been vertically integrating into the semiconductor industries.

John Blyler: The supply chain is really evolving.

Charles Shi: Yes, it is. In the past, system companies would buy from fabless companies, fabless companies would outsource to the foundry for wafer manufacturing, and the foundry would send the wafers to OSAT to do the package and then sell things all the way back to system companies.

Now, it’s getting much simpler and more efficient with the system companies designing chips, and at the same time, they create their own software. Then they send the order to the foundries, and the foundries both manufacture the chip and do the advanced packaging (3D-ICs, chiplets, etc.). As I mentioned earlier, it’s a much simpler value chain with many of the middleman activities cut out.

John Blyler: How does innovation fit into this return to a vertically integrated value chain?

Charles Shi: You will out-innovate through a system approach to regain competitiveness. The strength of the US is its tech ecosystem with companies like Apple, Google, Microsoft, Meta, Tesla, and such. These companies will probably be the drivers of semiconductor innovation going forward. To help foster this innovation, the US should help make it easy for the US ecosystem to collaborate and innovate – not necessarily working to create the next semiconductor factory.

John Blyler: Streamlining the semiconductor value chain and removing the middleman is a significant change. What does this mean for the EDA industry?

Charles Shi: EDA IP is a design enabler for companies to build their own domain-specific chips tailored to their application. In this way, these companies will enhance their competitive advantage. That is why EDA IP will likely continue to outperform the semiconductor industry, at least for the next several years, especially as emerging AI technology grows.

John Blyler: Might IP companies suffer as system companies start to create more of their own semiconductor IP?

Charles Shi: Eventually, system companies will create their own IP. But companies like Google, Menta, Microsoft, and others still rely on external IP providers and, in some cases, acquire IP companies. And getting bought by these big tech companies is a very lucrative exit strategy for external IP providers. I cannot predict what will happen in the distant future, but I believe these trends will be for the next 1 to 3 years.

John Blyler: Thank you.